By Ronald Penh

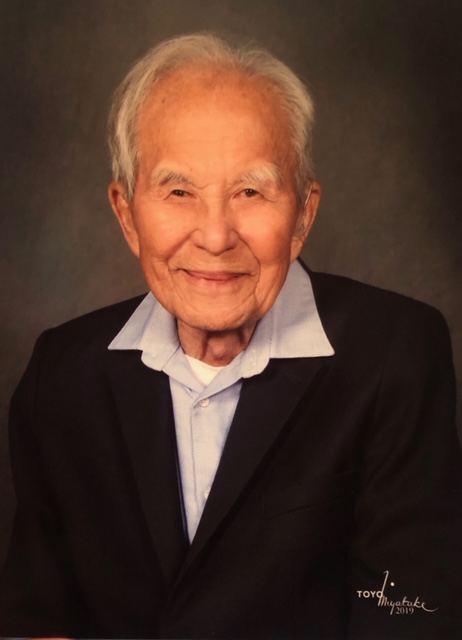

Bill Nishimura was born 100 years ago on June 21, 1920 in Compton, California. Within that century, he underwent some of the most pivotal, defining, and darkest moments of American history.

Some of his most defining experiences took place after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, in which laws were passed in America that sacrificed the civil liberties of Japanese-Americans in response to fears of them being espionage agents, despite a lack of hard evidence. The stripping of Japanese-American civil liberties was reflective of an extensive history of racist and discriminatory laws against Asian immigrants that existed since the restrictive immigration policies that were in place during the late 1800’s.

On February 19, 1942, president Franklin D. Roosevelt signed executive order 9066 which led to the internment of Japanese-Americans. Nishimura, his family, and 117,000 Japanese-Americans living in California, Oregon, and Washington were forcefully relocated to internment camps, most of whom were American citizens, according to an article from History.com.

However, Japanese-Americans were taken away as early as hours following the Pearl Harbor bombing, in which the FBI rounded up 1,291 Japanese-Americans that were community and religious leaders, without evidence and freezing their assets.

In January, the arrestees were sent to facilities in Montana, New Mexico, and North Dakota.

Before the forced relocation of Japanese-Americans, restrictions were already placed against them in their daily lives.

“We had, I believe it was, a 5-mile radius that we were able to travel, but beyond that we needed a special permit,” Nishimura said. “Like people who are taking produce to the market, they had to have a special permit for that.”

Nishimura’s father was the first of the family to be forcefully relocated to a camp. He worked at the Gardena Valley Japanese Association as the organization’s secretary-treasurer. The organization was important to the local Japanese in the area that spoke little to no english. The organization also entertained dignitaries from Japan. Those sorts of activities during the war, however, became subversive activity, which is what Nishimura believes led to his internment.

Nishimura was not there to experience his father being taken away, but recalled the story through the account of his sister.

“What she told me, was they checked inside the house, and then they told her that it’ll be a few hours and he’ll be back,” Nishimura said. “And it was three days later that we received a notice that he was held at the Tujunga Canyon CC Camp.”

Nishimura and his mother moved to Visalia, CA based on a rumor that those in the area would be safe from evacuation. Within months, however, Nishimura and his mother were forced to relocate to the Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona.

While at the camp, Nishimura studied Japanese language, in which his bilingual abilities were soon discovered and was asked if he wanted to join the Military Intelligence School.

Being forcefully evacuated to a camp, having his rights taken away, and losing thousands of dollars in crop sales, Nishimura was angry.

“My rights were taken away, and yet they wanted to have me serve in, for the country,” Nishimura recalled. “So I said, ‘No. You give me my rights, and then we’ll talk.’”

Another test to his desire to serve the United States came about through the “loyalty questionnaire” that took place in 1943. The responses were used to aid the War Department in recruiting Japanese-Americans for the war, as well as to aid the War Relocation Authority in the relocation of others.

Nishimura recalled his responses to questions 27 and 28, both of which were provocative questions considering the unjust circumstances that Japanese-Americans were facing while at the internment camps.

Question 27 asked if one was willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty whenever ordered.

Nishimura’s response was “no.”

Question 28 asked if one would swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any and all attacks by foreign and domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or disobedience to the Japanese Emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization.

Nishimura left the response with an “if.”

“‘If my rights were restored,’ I would answer this number twenty-eight, but otherwise, I would not answer,” Nishimura said.

The administration office had called him in to see if he was willing to change his answer to question 28, but Nishimura’s attitude towards the test would not change. He did change his answer to “no,” and was sent to the Tule Lake Segregation Camp as a result.

Nishimura was not the only one who answered “no-no” to questions 27 and 28 or resisted pleas for Japanese-Americans to pledge for the United States government.

He and others that decided to renounce their citizenship formed a group called the Hoshidan, a pro-Japanese group that was formed at the Tule Lake Segregation Camp. In an effort to dismantle the group, its members were relocated to different camps, in which Nishimura ended up in the Santa Fe camp along with his father

During Nishimura and his father’s internment at Santa Fe, the war ended in 1945 and the government began to ask if they wanted to stay in America or go to Japan. Nishimura didn’t know at the time who was victorious from the war. Surprised by the government’s leniency towards their decision to either stay in the US or go to Japan, he was under the impression that Japan had been victorious and wanted to go to Japan. But his father fell ill, in which they changed their minds, decided to stay in the United States, and were relocated to a camp in Crystal City, Texas. Nishimura was finally released two years after the war ended in 1947.

The quotes from this article come from an interview that Bill Nishimura did in 2000 at the Tule Lake Pilgrimage in Klamath Falls, Oregon. You can watch the segments of his interview by visiting the website http://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-densho-1000-119-1/.