Richard Castilla volunteered to fight

the Axis Powers in WW II, and what

he experienced, changed his life

By Christopher J. Lynch

Because they were on the other side of the international dateline when it occurred, VE – Day, or Victory in Europe Day, occurred not on May 8 as is recorded in the history books, but on May 9 for Seaman Richard Castilla and his shipmates in the South Pacific.

“Every year on that date, I pour myself a drink and have a toast” he says.

But the annual libation isn’t to celebrate the ending of the horrible war in Europe, it is to honor the memory of his shipmates that were lost on that tragic evening; that was the night their ship was hit by a Kamikaze and 37 sailors lost their lives.

Growing up in South Los Angeles, Castilla was only 17 when he did what many others his age were doing; he signed up to fight in World War II. It was Aug. 16, 1943, and he had just graduated from J H Francis Polytechnic High School a few months earlier.

“My brother had joined the Army a year or so earlier and was in the glider troops,” he recalls. “But most of the kids in the neighborhood kids were joining the Navy, including a buddy of mine, so we joined up together.”

It was not uncommon as Castilla remembers that times were different back then, especially people and their sense of duty to their country.

“Everyone was patriotic back then. I know that we are referred to as the ‘Greatest Generation,’ well I think we were the ‘We Generation.’ And unfortunately, today we seem to have the “Me Generation!”

After basic training in San Diego, Castilla was trained as a Fire Control Optical Range Finder and was responsible for determining the range to a target using an optical range finding device. His station was up on the flying bridge, the highest point on a ship.

That ship would become the USS England DE 635. Only 306 feet long with a slender 34-foot beam, the newly constructed destroyer escort had a crew of about 215 sailors. It also had a rather somber history when it came to its namesake.

“It was named after Ensign John C. England, who was on the Oklahoma when it was attacked in Pearl Harbor,” Castilla recites proudly. “England dove back into the ship three times and saved the lives of three of his fellow sailors, but on his fourth attempt, he never came back.”

Home ported in San Francisco, Castilla and his shipmates performed sea trials for several weeks up and down the coast of California until finally they were ready to enter combat. They shipped out on Valentine’s Day, 1944. It was a day Castilla will never forget, along with what the first few days at sea were like.

“I was seasick for about three or four days,” he recalls painfully. “And I carried a five-gallon bucket wherever I went to throw up into.”

Seasickness was a common malady for most of the newly minted sailors, but it had its comical moments as well.

Castilla laughs.

“So many guys were sick on the ship that they were puking into the trash cans. The cans smelled terrible but worse yet, when we hit rough seas, they would tip over and the floors would be covered in puke!”

They made a brief stop in Pearl Harbor which Castilla remembers as still badly damaged.

“It was very emotional, seeing all of the destruction,” he says.

Then they continued on to their theater of operation near Guadalcanal where they engaged in ‘picket duty’ to locate and destroy enemy subs. On May 13, they broke a Japanese code and the hunt was on to kill as many subs as they could.

And boy, did they!

On May 19, 1944. the England detected a Japanese sub designated I-16. They unleashed their salvos of Hedgehog Anti-Submarine Mortars and after a few misses, finally scored a hit with the fifth attempt. Four to six detonations of the Hedgehogs on the hull of the sub were followed by a large underwater explosion which was so powerful it lifted the England’s fantail and knocked men off their feet. Debris began floating to the surface 20 minutes later. The following day, a three-by-six-mile oil slick marked the location on the calm surface of the Pacific.

But the crew of the England were just getting started.

“We sunk six Japanese subs in just 12 days,” Castilla says proudly. “It’s a record that’s still standing to this day, and our ship received a Presidential Unit Citation.”

There was no time to celebrate though as the final push toward Japan and victory were in the crosshairs. They continued their patrols and working their way toward their eventual target.

Slightly less than a year went by and Castilla and the crew of the England found themselves at the U.S. Navy’s secret base at Ulithi, 1,300 miles south of Japan. Hundreds of other ships were docked there and staging for the coming siege of Okinawa. Then, on April 1, 1945, one of the bloodiest battles in the Pacific was launched.

It was early evening on May 9, while supporting the battle for Okinawa that the England’s radar spotted three Japanese Aichi D3A’s dive-bombers (also known as ‘Vals’) heading inbound to attack them.

Luckily for Castilla and his crewmates, two Marine planes were patrolling nearby and were able to shoot down two of the enemy aircraft. But a third one, a Kamikaze, got through and hit the ship, directly under Castilla’s station on the flying bridge.

“It was an incredible explosion,” he remembers, “And devastating. Twenty-seven crewmen were killed instantly, and 10 more were blown off the ship into the water, never to be found again.”

Fire from the explosive and fuel-laden plane raced up the side of the structure toward Castilla and some fellow seamen. They had to climb out of the flying bridge and come down the other side in order to stay alive. Then they scrambled back to the other side of the ship to assist with the firefighting effort, which took several hours.

The England survived but was badly damaged and had to return stateside for repairs. By way of San Diego, they made their way down the coast and went through the Panama Canal, which Castilla says was very interesting.

“We always had to travel with no lights at night because of the war in the Pacific. But when we went through the canal and were on the Atlantic side, we could finally turn on our lights, because the war in Europe was over.”

After docking at the shipyards in Philadelphia the crew was given some much-needed leave. It was during his time home, Castilla heard that the Japanese surrendered. World War II was finally over.

He discharged out of the Navy in 1946 and took a job at General Motors in nearby Southgate. He rose quickly in the ranks and in 1957 purchased a home in Gardena, where he still lives to this day. Along the way, he married and had four children, eight grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren.

A proud part of the “We Generation.’

Author and Gardena resident Christopher J. Lynch is the author of the award winning One Eyed Jack crime novel series which is set in the South Bay. If you know of a Gardena veteran who would like to be interviewed for the Gardena Valley News, you can contact Christopher at www.christopherjlynch.com

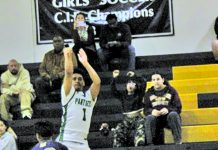

CAPTION

LOOKING BACK—Seaman Castilla, today, holds a model of the Val, the Kamikaze plane that hit his ship on VE-Day.

Photo by Christopher Lynch